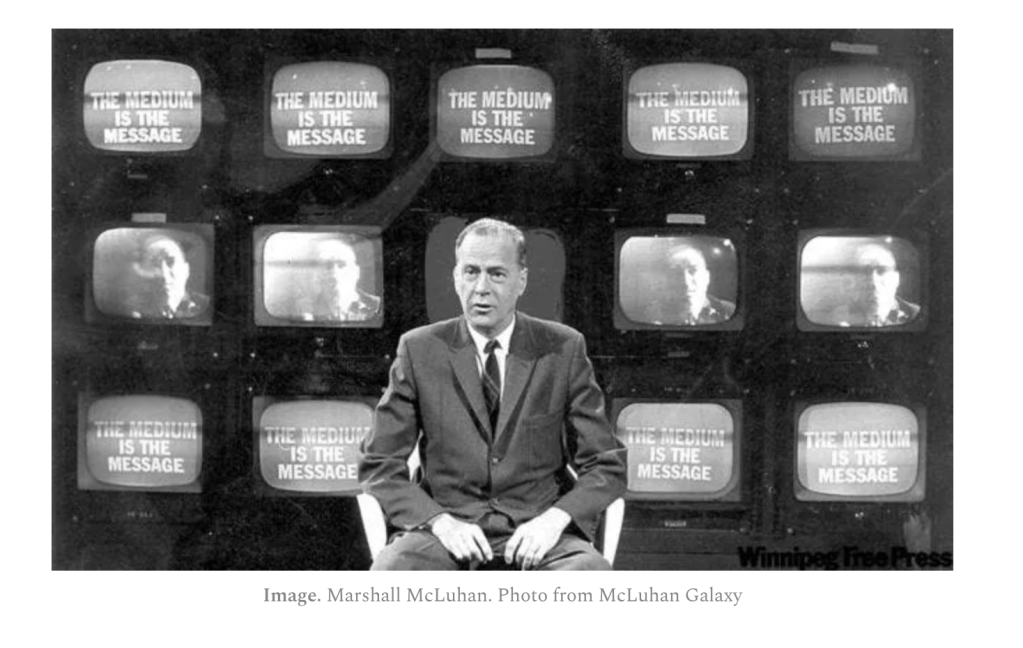

What is a cliche? It is a phrase, regardless of its truthfulness or lack of, that we have heard ad nauseam. Many come to mind: the grass isn’t always greener on the other side, you can’t judge a book by its cover, etc. They are, of course, culturally dependent with every group of people having popular phrases repeated too many times. At ITP, I learned that Marshall McLuhan wrote that The Medium is The Message. That was a profound reckoning when I heard that last year, a statement that really made me investigate the embedded directives baked into whatever technical form I use to tell a story. Now, I’ve heard that phrase brought up 100 times here, nodding along. I find myself doing that a lot recently when it comes to current events. Perhaps the World is one of Cliches at this particular moment in history. Not just because things feel overdone, overwrought, and oversimplified. Cliches are a message and a medium of their own. The etymology of the word cliche comes from France (those darn French again), from the word clicher, which means “to click.” The clicking refers to the sound of a wooden block pressed into molten metal in order to print words or images repeatedly with ease. Thus, cliche is an onomatopoeia of an easily repeated (therefore, overly repeated) phrase.

In this AI age, we are at the mercy of cliches. So much is going on in the world. So many issues that need facing. So many traumatic things we’re witnessing. So much information deluging our minds that we can’t properly analyze each and every incident. Instead, oversimplified cliches act as a placeholder for analysis that we are too weary and confused to form. Neil Postman, a student of Marshall McLuhan, writes in his book Technopoly that inherent in the medium of computers is abstraction. Computers separate information from context and extrapolate data. They are fine tools for research, but the impressive amount of information and lack of regulatory/cultural restraint leads people to be ruled by the tools. We are Data now, run through the processor of algorithms served up in a nice excel sheet by adtech companies. We know this. They know that we know. And we do it anyway.

Through social media, social interaction has shifted to a paradigm of data extraction. We do not intend to profit off of each other like the adtech companies do, but our discourse is colored by categorizing people into whatever cliche devices someone uses and if they align with ours. This must take place to determine if you can actually have a reasonable, reciprocal conversation with someone and to avoid dealing with unnecessary conflict. Also to avoid any narcissist wanting to use you as a sounding board for their own ideas, another feature of the digital ecosystem that rewards someone for talking about themselves all the time. The social media world has made us better at surveillance, scoping each other out for any threat (we know an overwhelming amount exist, we have the data) and concealing any part of ourselves that might be “too much” or abrasive to interaction. Because the world is too much as we see all the time, unrelenting. Why should we be overwhelming to other people too? So we detach from each other as we have attached from our crumbling institutions, as Adam Curtis notes in his 2016 documentary Hypernormalisation.

So what do we do? How do I make a social media or product or cyberspace that makes people kinder and happier? I feel inclined to cheat and say get off the computer and go outside. Aside from that, Professor Nicholas Smyth (by way of Postman) argues that we need to re-establish our cultural norms to constrain and direct technology. We need to develop a collective language for us to take action together. For the sake of these norms, I have made an embedding to determine if someone is normal. This way, we can moderate if someone doing something is acceptable and within the bounds of society or some freaky stuff that should direct them to a therapist/proper institution. It’s a start.

Leave a comment